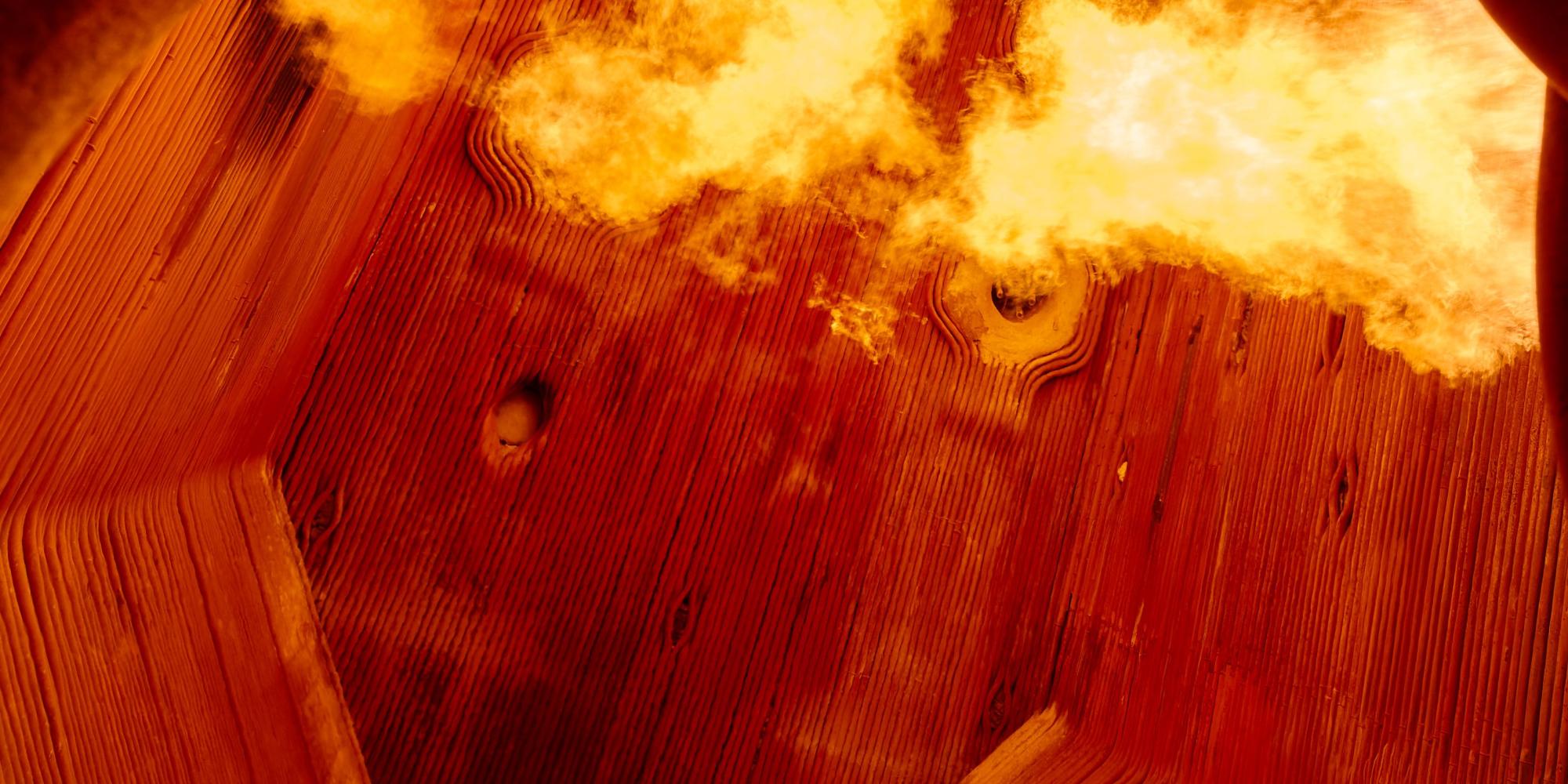

The Oxy-kraft recovery boiler project aims to enable the operation of pulp and paper recovery boilers in oxy-firing mode. This could provide a new approach to bioenergy carbon capture compared to the current, costly method of capturing carbon from flue gases.

Carbon capture is an important component in tackling climate change.

“They are very big, these installations, and they burn a huge amount of black liquor. Normally, this is burnt with air in conventional recovery boiler installations with the purpose of recovering the pulping chemicals for reuse and at the same time producing steam for the pulping process and surplus electricity for the grid. But in our project, we are talking about oxy-firing and oxy-combustion, so that is why it is called Oxy-kraft,” explains Patrik Yrjas, Senior Researcher at the Faculty of Science and Engineering at Åbo Akademi University. He is the coordinator of the Oxy-kraft consortium. The partners in the project include KTH in Sweden and the University of Zaragoza in Spain. Currently, four PhD students are working on the project: one in Sweden, one in Spain, and two in Finland, and industry partners are also involved.

Oxy-combustion means that black liquor is burned using a mixture of oxygen and recirculated flue gas. The nitrogen in the air is no longer present in the combustor or in the flue gas, while part of the flue gas is recirculated to control burning temperature.

“When we burn fuel with only oxygen and no nitrogen, the gas that leaves the combustor is mostly CO₂ and water vapour. Because the CO₂ has a high concentration, it is easier to efficiently capture the CO₂ from an oxy-fired boiler than from an air-fired boiler,” Yrjas says.

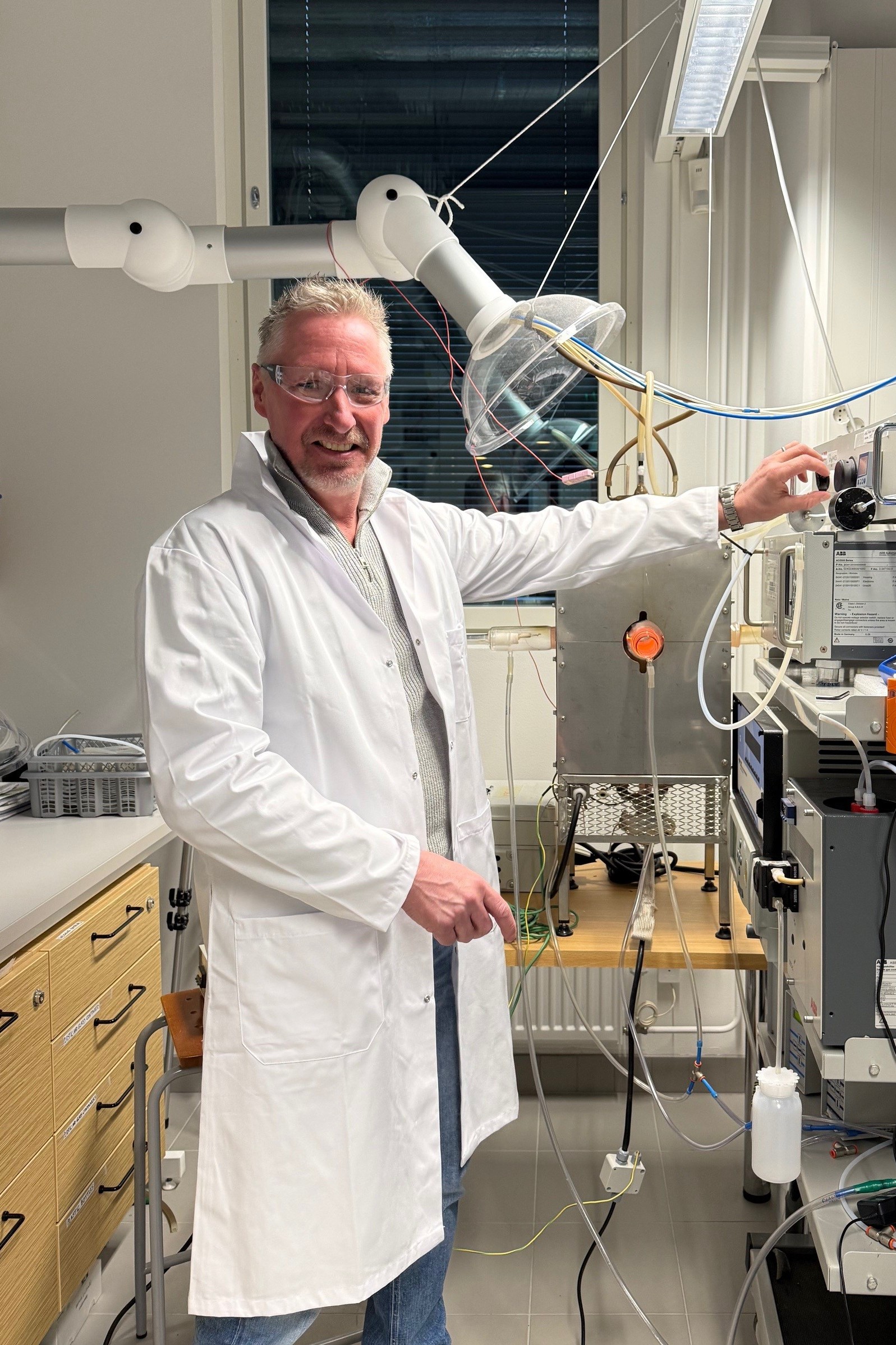

Senior researcher Patrik Yrjas, at the Faculty of Science and Engineering at Åbo Akademi University, is seen here behind a metallic box with a glowing opening, which is an experimental reactor. The small black liquor samples are burned in it under different conditions, and the flue gases are led to gas analysers (CO, CO₂, SO₂, NO/NO₂). During the burning process, the particle is video recorded. Photo: Sara Hagman

Less CO₂

The end result is less CO₂ released into the atmosphere.

“This process will result in significantly less CO₂ emissions from these boilers, which means this technology could have a role to play in combatting climate change. We enable CO₂ capture from the process, and since the black liquor is a biomass, it would be counted as negative emissions,” Yrjas adds.

From an air-fired boiler, the CO₂ concentration in the flue gas is about 15 to 20%. In oxy-combustion, it can be around 80%, depending on the conditions. The rest is mostly water.

“The whole idea is to burn with oxygen and not involve nitrogen or air. Normal air has about 21% oxygen and 79% nitrogen. Now we leave out the nitrogen and use only oxygen together with recirculated CO₂. To burn with pure O₂ would result in too high temperatures.” Yrjas says.

Laboratory studies

Since it is very difficult and expensive to study the combustion of black liquor and the influence of different operating parameters in large installations, the experimental part is only carried out in the laboratory.

“We use very small droplets or samples of this black liquor in our experiments when we study the combustion behaviour. The samples we use are only about 10 milligrams,” he explains.

Vital partnership

According to Yrjas, being part of the Clean Energy Transition partnership has been vital for Oxy-kraft.

“This organisation makes it possible to finance this research. It would not be possible otherwise.”

Precisely because of the high costs, it has not yet been possible to get industry to finance the technology, but he remains hopeful that this could happen in the future.

Yrjas points out that the installations are very large, so not many exist.

The Oxy-kraft project is scheduled to run until the end of 2026, but there are hopes that it could be extended until 2027. “At the moment, we are looking into different possibilities to continue this research beyond that time.”

The hope is that if an old recovery boiler became available and there was a need to build a new one, the old unit could be used to test the technology in a full-scale environment.

“I think the advantages would be so great that I would expect we would get funding for this. However, at the moment, the companies remain somewhat hesitant because of the high costs involved,” Patrik Yrjas concludes.

About the project

The project is led by project coordinating partner Finnish Åbo Akademi University, and the consortium also includes partners from Sweden and Spain.